<< Return Home

<< Regrese a la página principal

|

>> Watch video about the retablo ayacuchano <<

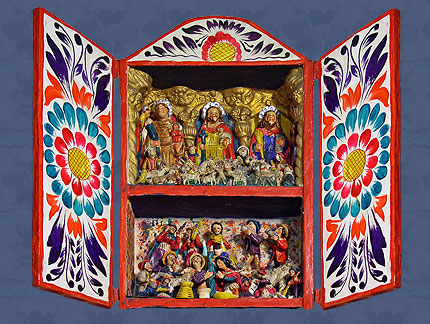

The retablo created by Nicario’s father represents a transformation into the contemporary retablo ayacuchano. It represents a transition into more secular and varied types of scenes, beyond just representing a particular set of saints. It also represents a change in function from magical-religious to folk art. In this so-called second generation, the retablo’s primary value is artistic. In the 1970s the retablo form underwent a further development to represent daily life. The retablo artist Joaquín López Antay, in response to requests by the collector Alicia Bustamante, changed the figures in the lower level of some sanmarcos to represent genre scenes (Ulfe 2005).

Alicia Bustamante, one of the first collectors of Peruvian popular art, is acknowledged as the person who transformed the cajón sanmarcos into the modern retablo form. Starting in 1941, she (and others), who were associated with Peru’s indigenist (indigenista) pro-Indian movement, encouraged the artist Joaquín López Antay to expand the themes in his work to include representations of the daily life of the people. This was initially to serve the perceived desires of consumers. She also is credited with changing the name from sanmarcos to retablos “because of their resemblance to the altars in the Catholic churches (Ulfe 2005:47). López Antay, accompanied by other local artists, thus renewed the art form in a form that continues today. In 1975, Joaquín López Antay was awarded the National Prize in Art from the Peruvian National Institute of Culture, which was the first time that this prestigious award had been given for a native Andean art (Tamara R. Williams, “The Retablo Ayacuchano: A Case Study in the Evolution of a Popular Art Form.” In Carol Damian and Steve Stein, eds., Popular Art and Social Change in the Retablos of Nicario Jimenez Quispe. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2004: pp. 1-12; María Eugenia Ulfe, Representations of Memory in Peruvian Retablos, Ph.D. dissertation in Anthropology, George Washington University, 2005.).

Of the many Ayacucho retablo artists, four were awarded Peru’s National Grand Award Amautas [masters] of Peruvian Handicrafts”: Jesús Urbano Rojas (1993); Heraclio Núñez Jiménez (1997), Florentino Jiménez Toma (1998), and Julio Urbano Rojas (2002) (Ulfe 2005:62).

>> Mire video sobre el retablo ayacuchano <<

El retablo creado por el padre de Nicario representa una transformación al retablo ayacuchano contemporáneo. Este r epresenta una transición a escenas mas seculares y variados mas allá de la representación de los santos patrones. También representa un cambio de función de lo mágico-religioso al arte folclórico. En lo que se llama la segunda generación, el valor principal del retablo es artístico. En los anos 1970s, la forma del retablo se desarrollo para representar la vida cotidiana. El retablista Joaquín López Antay, respondiendo a pedidos por la coleccionista Alicia Bustamante, cambio las figuras en el nivel inferior de algunos sanmarcos para representar escenas costumbristas (Ulfe 2005).

Alicia Bustamante, una de la s primera s coleccionistas del arte peruano popular, es reconocida como la persona quien impulso la transformación del cajón sanmarcos al retablo moderno. Comenzando en al añ o 1941, ella y otros coleccionistas, quienes eran asociados con el movimiento peruano indigenista, sugirieron al artista ayacuchano Joaquín López Antay que expandiera los temas de sus cajones para incluir las escenas costumbristas representando la vida diaria del pueblo andino. Ella también es reconocida por haber cambiado el nombre del cajón sanmarcos al retablo “por su semejanza a las capillas en la iglesias católicas” (Ulfe 2005:47). Joaquín López Antay, acompañado por otros artistas, renovó el arte hacia una forma que continua hasta hoy en día. En 1975, fue premiado con el Premio Nacional de la Cultura, del Instituto Nacional de Cultura del Perú, la primera vez que este premio fue entregado a un arte tradicional andino ((Tamara R. Williams, “The Retablo Ayacuchano: A Case Study in the Evolution of a Popular Art Form.” In Carol Damian and Steve Stein, eds., Popular Art and Social Change in the Retablos of Nicario Jimenez Quispe. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2004: pp. 1-12; María Eugenia Ulfe, Representations of Memory in Peruvian Retablos, Ph.D. dissertation in Anthropology, George Washington University, 2005.).

De los muchos retablistas ayacuchanos, cuatro han sido premiados con el “Premio Gran Amauta (maestro) de la Artesanía Peruana” son: Jesús Urbano Rojas (1993); Heraclio Núñez Jiménez (1997), Florentino Jiménez Toma (1998), y Julio Urbano Rojas (1992) (Ulfe 2005:62).

|